AI tools are changing how we build software. The question is not whether they make us faster. They often do. The question is whether they help us be effective: making the right decisions for the long-term system.

This post was triggered by the video We Studied 150 Developers Using AI (Modern Software Engineering), which discusses a study on the effects of AI tools on productivity and long-term maintainability.

What the video/study claims

The main points discussed in the video (paraphrased):

- Productivity goes up: AI users were reported to be ~30%–55% faster during initial development.

- Maintainability does not automatically get worse: the study did not find a significant difference in maintainability / maintenance cost between AI-assisted and non-AI code (in that setup).

- AI amplifies the user: strong engineers tend to produce more idiomatic, boring, maintainable solutions; weaker engineers can produce bigger messes faster.

- Two risks were explicitly called out:

- code bloat (generating too much code)

- cognitive debt (stopping to think less, shipping understanding debt into the codebase)

Even if you disagree with parts of this, it’s a useful frame: AI changes the speed of production, but it does not remove the need for engineering judgment.

The “do-my-work button” temptation

A lot of AI adoption rhetoric implicitly assumes there is a simple “do-my-work button”. In practice, this is where things start to go wrong.

If the primary goal becomes “get something out of the door quickly”, AI is a perfect accelerant:

- more code

- more change surface

- more hidden coupling

- more review load

You can get fast progress on paper while silently increasing the cost of everything that comes after.

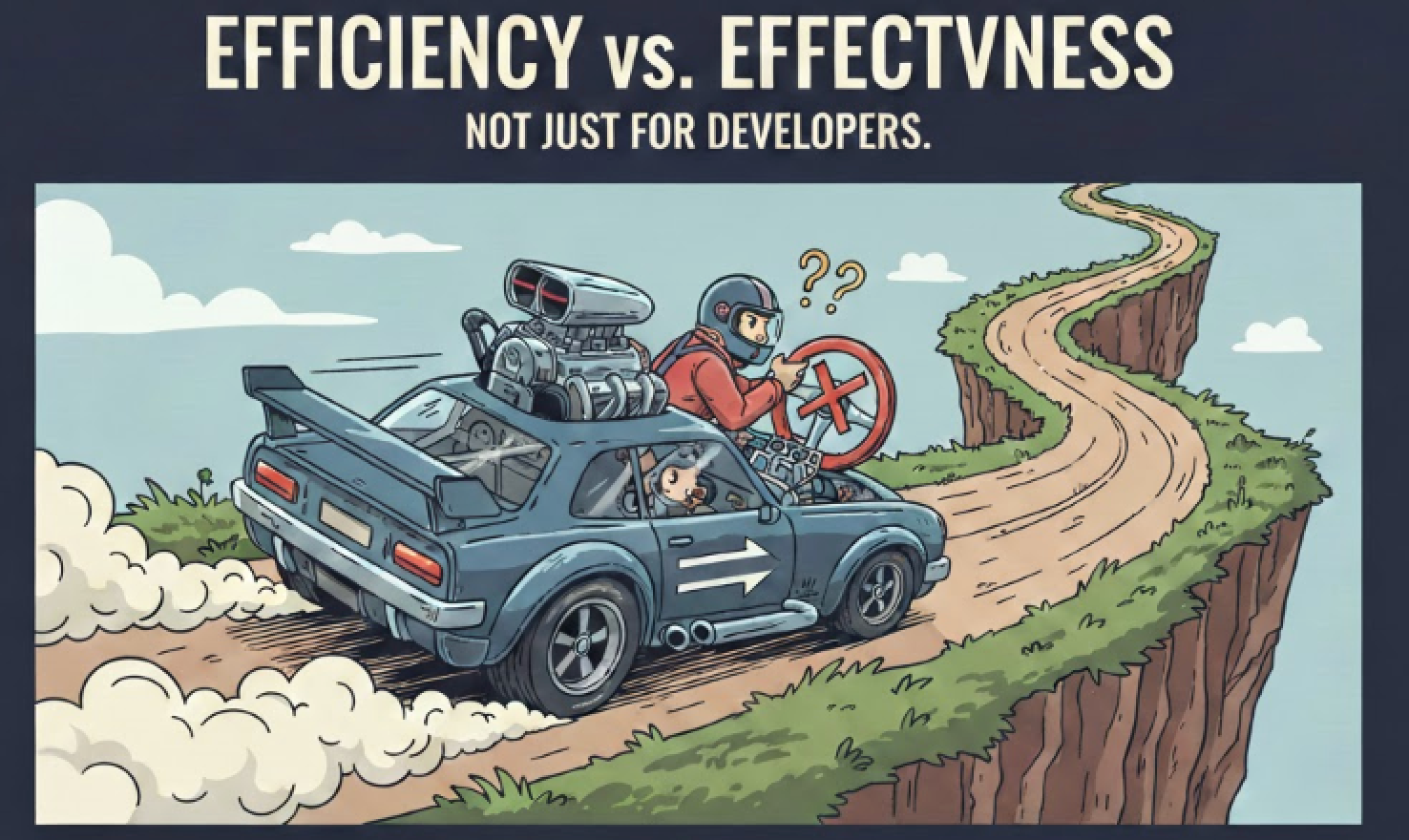

Efficiency vs. effectiveness (why this is not a developer-only topic)

In professional software development, efficiency without effectiveness is not a win.

Two failure modes look similar at first glance but are very different in outcome:

- Shipping the wrong thing quickly is still failure (just faster).

- Shipping the right thing slowly can still be acceptable if you learn and compound.

This is why AI adoption is not just a tooling choice. It is also a leadership and decision-making topic:

- What do we reward?

- What do we measure?

- Do we optimize for throughput, or for outcomes?

Teams are not individuals

An individual working alone can optimize for speed and personal context.

Teams have different constraints:

- shared understanding

- reviewability

- predictable delivery

- maintainability under rotation and time

- onboarding of new/junior developers

- operating the system in production (incidents, on-call, debugging)

A common real-world pattern looks like this:

A feature is generated quickly, shipped quickly, and “works”. Two weeks later someone else needs to modify it. The code is long, plausible, and hard to reason about. The team spends more time rebuilding understanding than the original generation saved.

That is not “technical debt” in the classical sense of knowingly trading quality for speed. It is often cognitive debt: the system’s complexity grows faster than the team’s shared model of it.

What to take from the study framing

If the study result holds in general (speed up, no immediate maintainability penalty), then the interesting takeaway is not “AI is safe”.

The interesting takeaway is:

- maintainability is not only a property of the code

- maintainability is a property of the system of work: decomposition, review, tests, ownership, incentives

AI improves the ability to produce code. It does not automatically improve the ability to decide.

Practical guidance (context, communication, collaboration)

If you want AI to increase effectiveness (not just output), the key is to avoid isolated “AI-assisted” work.

AI makes it easy for an individual to generate a lot of plausible work very quickly. But software is a team sport, and in a company there is usually a lot of hidden leverage: domain experts, senior engineers, product, support, ops, security, and people who have seen the same failure modes before.

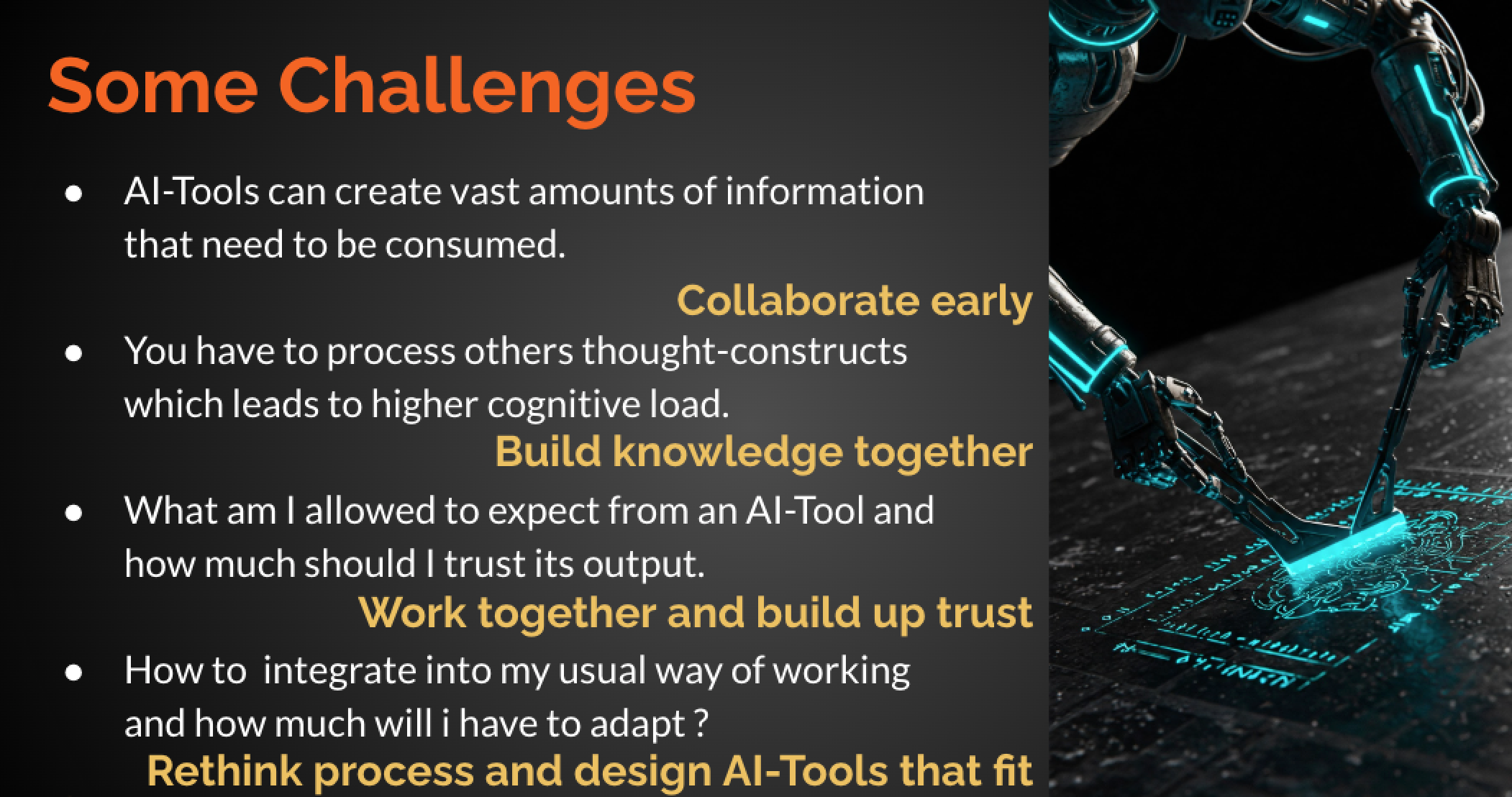

A useful frame from the slide below is: Challenges → Collaboration-oriented countermeasures.

Challenges and how to avoid them

-

Challenge: AI tools can create vast amounts of information that need to be consumed.

- Avoid it: Collaborate early. Share the prompt, intent, and early outputs quickly.

- Practical examples:

- post “here’s the direction + why” in your team channel before you generate 20 pages of output

- run a short alignment call before you commit to an approach

-

Challenge: You have to process others’ thought-constructs, which leads to higher cognitive load.

- Avoid it: Build knowledge together. Use AI outputs as shared artifacts, not personal notes.

- Practical examples:

- co-create a short design note (problem, constraints, options, decision)

- pair/mob on the first slice to establish the mental model

-

Challenge: What am I allowed to expect from an AI tool, and how much should I trust its output?

- Avoid it: Work together and build up trust. Calibrate trust as a team with explicit checks.

- Practical examples:

- agree on “trust boundaries” (what must be tested/reviewed/benchmarked)

- compare AI suggestions against existing system conventions and production constraints

-

Challenge: How do I integrate this into my usual way of working, and how much will I have to adapt?

- Avoid it: Rethink process and design AI tools that fit. Integrate AI into your existing quality gates and collaboration loops.

- Practical examples:

- make AI a step inside PRs/reviews (summaries, risk lists, test suggestions), not a parallel workflow

- standardize prompts/templates so outputs are consistent and reviewable

The deeper point

AI amplifies individuals — but companies win through shared context, communication, and collaboration. The fastest way to lose effectiveness is to let AI push work into private branches of understanding. The fastest way to gain effectiveness is to turn AI into a team tool that strengthens shared decision-making.

Closing

AI can make us more efficient.

The real work is making sure we stay effective: choosing the right problems, making good trade-offs, and building systems that remain understandable to the team.